Some nuclides presented in this calendar have a bad reputation. In some cases well deserved perhaps, and in some cases the nuclides might have gotten the blame for our failures.Today’s nuclide is such a case: Plutonium-239, to many it’s associated with nuclear weapons, but actually offering much more than destruction.

In the dawn of the nuclear era, during the Manhattan project, it was soon realized that it is not easy to acquire large quantities of fissile material. The only naturally occurring nuclide, uranium-235, makes up about 0.7 % of the uranium on Earth, which is mostly uranium-238. Increasing this fraction by isotopic enrichment requires lot’s of energy and time. Add to that problem that the known uranium resources in the world were very limited at the time, and therefore it was hard to imagine that large scale use of civil nuclear power would be feasible. All of the scarce uranium-235 might well be needed in the nuclear arms race that was sure to come.

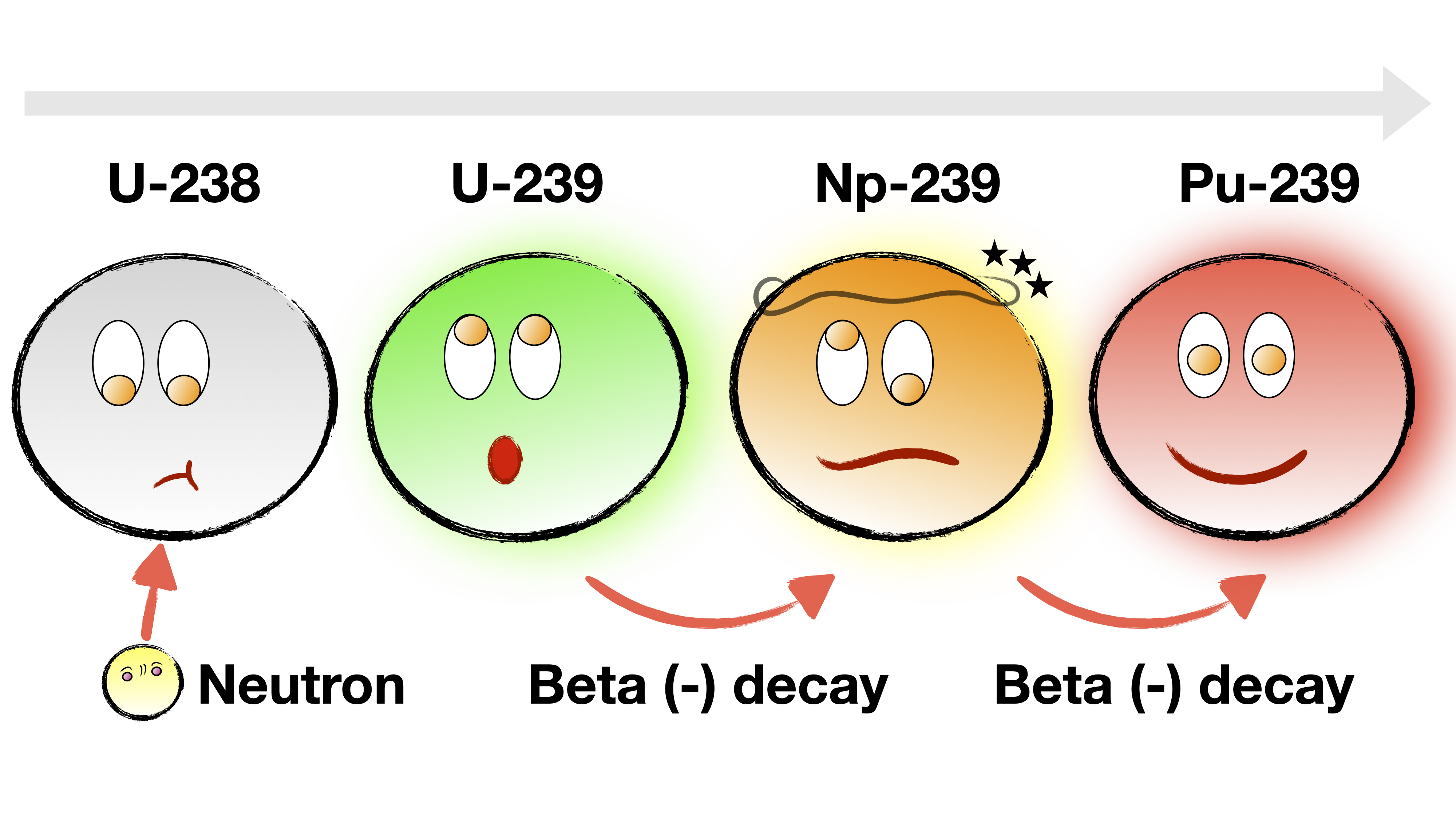

Plutonium-239 was early envisaged as a solution to the scarcity problem of uranium-235. Pu-239 is not abundant, but it can be produced by irradiating uranium-238 with neutrons, and therefore it is also produced in any uranium-fuelled nuclear reactor, due to its high concentration in the core. The neutron capture produces uranium-239, which beta decays within minutes to a new element, neptunium-239. In turn, this beta decays within a few days to our nuclide of the day, plutonium-239.

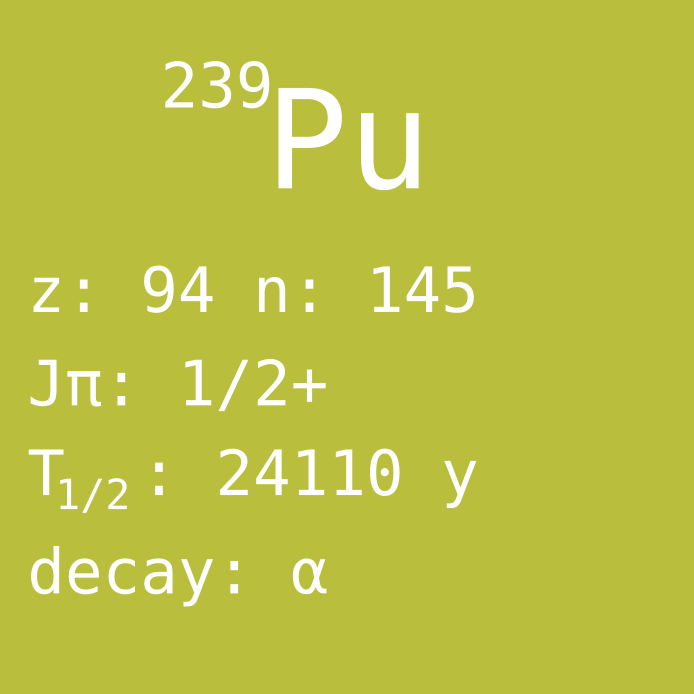

Plutonium-239 has an even proton number, and therefore as we have discussed before, it is relatively stable, with a half-life of 24 000 years. On the contrary, it has an odd number of neutrons, which causes it to be fissile with slow neutrons. When the neutron is absorbed, the binding energy of the nucleus suddenly increases, meaning that there is excess energy available to split the nucleus in two. So therefore, in any uranium-fueled reactor some fissile plutonium is created, and this is called breeding. While Pu-239 is fissile, the U-238 that can be used for breeding, is called fertile.

The plutonium had already found use early in the Manhattan project in one of the two first nuclear weapons. How come that we always are so fast to adopt new knowledge in the form of new weapons? Well, in the eyes of the reactor physicists Enrico Fermi and Walter Zinn, plutonium also opened the door to peaceful nuclear power. If one can run a reactor on plutonium from breeding, one could foresee a hundredfold increase in the energy resources available in natural uranium, if compared to using only U-235, with the isotopic abundance of only 0.7 %. This was envisaged to make the scarce uranium sufficient for also the peaceful use of the atom, in parallel to the military use.

However, there were challenges: For their plutonium dreams to be realized, so-called breeder reactors would be needed, which create as much fissile material as it consumes, or even more. The existing reactors, at that time only used for nuclear weapons production, could breed some plutonium, but they wasted much more of the precious uranium-235, than the amount of plutonium that was gained. So it was still a net loss affair in fissile material. To actually open the door for a civil plutonium fuel cycle, this would need to change.

So what is the physical condition to satisfy if wanting a breeder reactor? Technically, for every fission reaction, a number of neutrons are emitted, one of which needs to induce fission in another nucleus, otherwise the chain reaction fades away and the reactor shuts down. In addition, for breeding, one neutron needs to transmute a “fertile” nucleus, such as the uranium-238, to a “fissile”, such as Pu-239, for every fissile nucleus consumed. One may think that this is an easy feat, because there’s more than two neutrons emitted per fission, but in fact, some are inevitably lost (absorbed by other materials such as the coolant, or simply leaving the reactor without entering any interaction), making this an engineering challenge.

In particular, the breeder reactor of the uranium-plutonium fuel cycle cannot have a moderator. You may remember from earlier days of this calendar, that having a light-element moderator surrounding the fuel increases the reactivity, and it was therefore used in early reactors, as well as in the vast majority of reactors today. The problem is that with this approach, there are not enough neutrons for breeding. Once a Pu-239 nucleus splits, there is seemingly more than enough neutrons emitted, about 2.8 on average. However, of the neutrons absorbed in the Pu-239, only about 60% causes fission, the rest are transmuting the nucleus to non-fissile plutonium-240. Thereby, we worsen the neutron economy and a self-sustained uranium-plutonium breeding cycle is made impossible. So, while any moderated reactor will gain some fissile fuel by breeding of plutonium-239, this just slightly improves the fuel efficiency. It’s still far from self-sufficient on fissile fuel.

The solution that Fermi and Zinn came up with was a fast reactor. By removing the moderator, it is more difficult to obtain the self-sustaining chain reaction, and one needs more fissile material to do this. But the reason that it’s difficult to obtain the criticality is because of the relatively larger absorption in the fertile nuclei, and this is not a bad thing if desiring breeding. And the real beauty of this path is that more neutrons are emitted in the fissioning by fast neutrons, and in addition, the neutrons that are absorbed are more likely to induce fission. Not in all nuclides, but in the plutonium-239 this is the case, as well as in most of the fertile nuclei. The fast neutrons carry a lot of energy, which helps to push some non-fissile nuclides over energy thresholds, where they can also contribute to the fission chain reaction.

By the end of the forties, the construction of the Experimental Breeder Reactor (EBR-I) started for proving the principles. This reactor was cooled by molten metal (NaK) instead of moderating water. Beside validating the theory that breeder reactors could be made, they also at the same time connected turbines and generators to the reactor, for the first time demonstrating the production of electric power from a nuclear power plant. EBR-I started operation in 1951. Even if it was only a few light bulbs that were supplied with its electricity.

By increasing the energy resources by two orders of magnitude, fast breeder reactors are a great leap for sustainable nuclear power, and our pioneers of nuclear energy also made a great climate mitigation impact. Unfortunately, the technology demonstrated in EBR-I turned out not to be needed for expansion of a civil nuclear power sector. This is because the reserves of uranium turned out to be a lot larger than initially known, and in parallel the uranium enrichment technologies were developed at great speed. Since building light-water cooled and moderated reactors with enriched uranium seemed more attractive than breeder reactors, unfortunately the sustainability dream was quickly dropped.

Still today, there are uranium stockpiles for a century at current consumption rate in the moderated reactors, and if the demand would increase, new uranium reserves might be available (also there are some plans to get uranium from the oceans). Nevertheless, the uranium remains a finite resource, and one has to admit that using all of the mined uranium, instead of just the most attractive 0.7 % of it, would be much more resource effective. As said, this would make nuclear power more sustainable, and one could continue the operation for thousands of years with only the uranium stockpiles (of mainly U-238) that we already have (also using spent fuel from traditional reactors, which already contains some plutonium), removing the need for mining or prospecting of new uranium resources for a very long time to come.

Since sustainability is hotter now than in the 60s, plutonium might need to be reevaluated, it can be used to satisfy the peaceful energy demands of humankind. It needs to be mentioned that there are many other aspects to consider in comparisons of nuclear fuel cycles, and there are also advantages of continued use of our common, moderated, light water reactors. So far, plutonium is recycled in only a few countries in the world, and only a handful of reactors are fast neutron reactors. But in the end it will be difficult to defend wasting 99% of the energy in a raw material, and the time for fast reactors will probably come, sooner or later.

© 2020 Zs. Elter, P. Andersson and A. Al-Adili