You probably all remember the periodic table of the chemical elements from school, if you were lucky you might have even seen one every day hanging on the classroom's wall. These chemical elements are substances that we cannot break further by chemical reactions. They are made of tiny atoms having identical number of protons. For example if you had a piece of pure iron (let say 1 kilo, because you don't wanna do heavy lifting just before Christmas), that would be an example of a chemical element, made up of roughly 10000000000000000000000000 atoms. That is 25 zeros there.

Now, these atoms consist of a seed, the nucleus (plural would be nuclei) and electrons buzzing around it. How these atoms can participate in a chemical reaction (for example to get rust on our iron) is mostly determined by the number of protons within the nucleus. So really, at this level we mostly care about positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons.

If you were a pupil now, and your school's periodic tables were up to date, you would observe 118 elements on it: 94 naturally occur naturally, and the rest were synthetically created. They are like toys for some scientists. Or maybe the equipments used to synthetize these are the toys, and these are more like ice cream.

Life seems quite simple with only having a couple of hundred of these elements, certainly we can even do some chemistry with them, make an omelette and such. But the fun part begins when we realize that the nucleus may have some other particle in it besides protons: the neutrons. That's when we start to talk about nuclides which are atoms characterized by their number of protons and their number of neutrons. They are also characterized by their energy state (but we will leave that for the hard-core scientists for now). The particularly interesting thing for us are the isotopes: the variants of a chemical element, that have the same amount of protons, and the only difference is in the number of neutrons.

Let's pick up that lump of iron again, if we examine it a bit closer, we don't just see that it has that huge amount of atoms in it, but we could also see that there are four different types of atoms, differing only in the number of neutrons within the nucleus. Now this seemingly subtle variation can make quite big differences when we look into nuclear properties and nuclear reactions. For example, it can affect whether an isotope is radioactive. For instance, breathing some oxygen with eight neutrons is quite a customary habit for most of us, but you probably would like to avoid sipping an oxygen with only seven neutrons, since that is strongly radioactive (we will talk about that in a moment). The fun part is that, as we said before, the chemical properties are mostly determined by the number of protons in an atom, so the various isotopes of the same element participate in chemical reactions in the same way: your lungs will not care whether you are sucking on stable or radioactive oxygen, they will send it around in your body anyway.

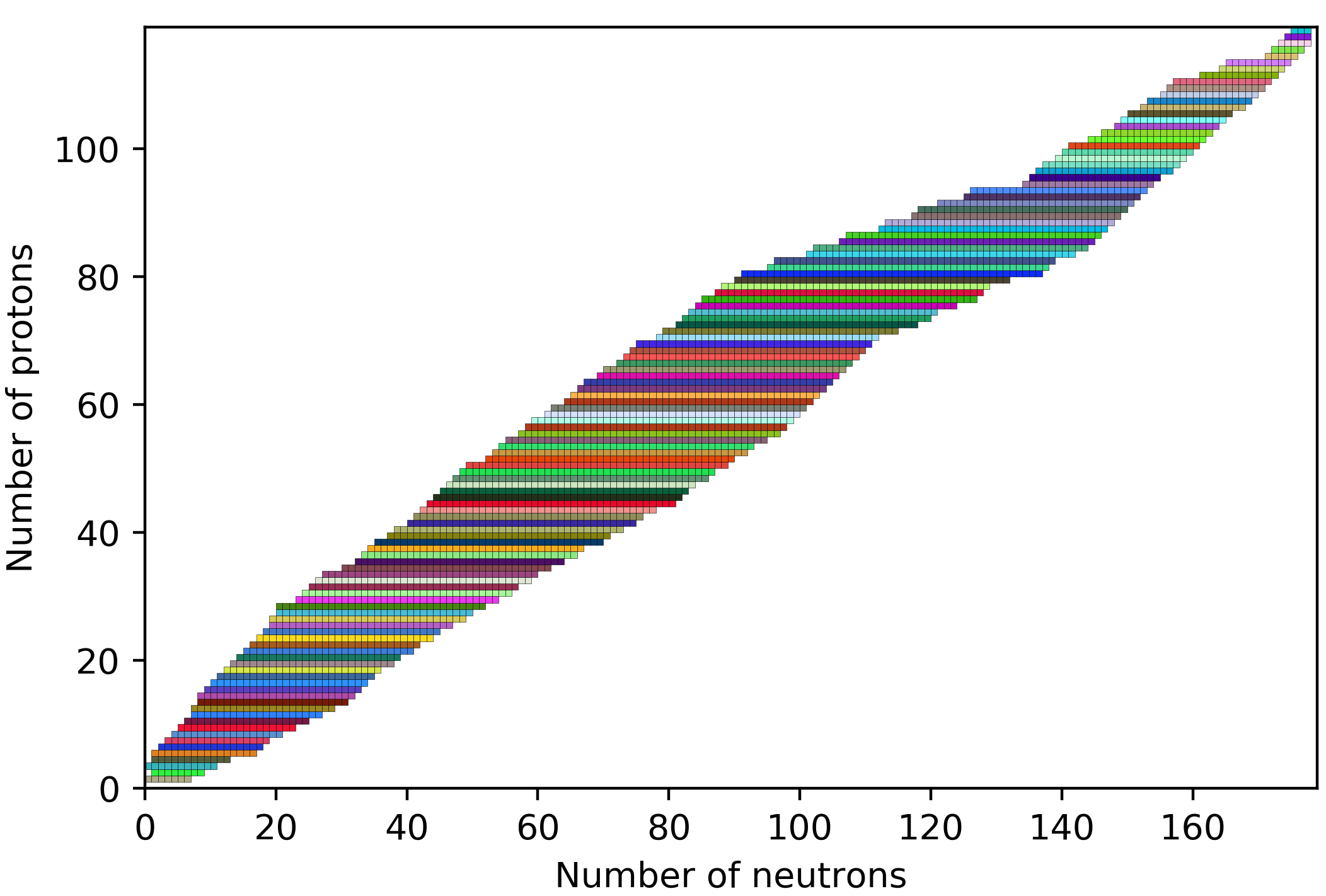

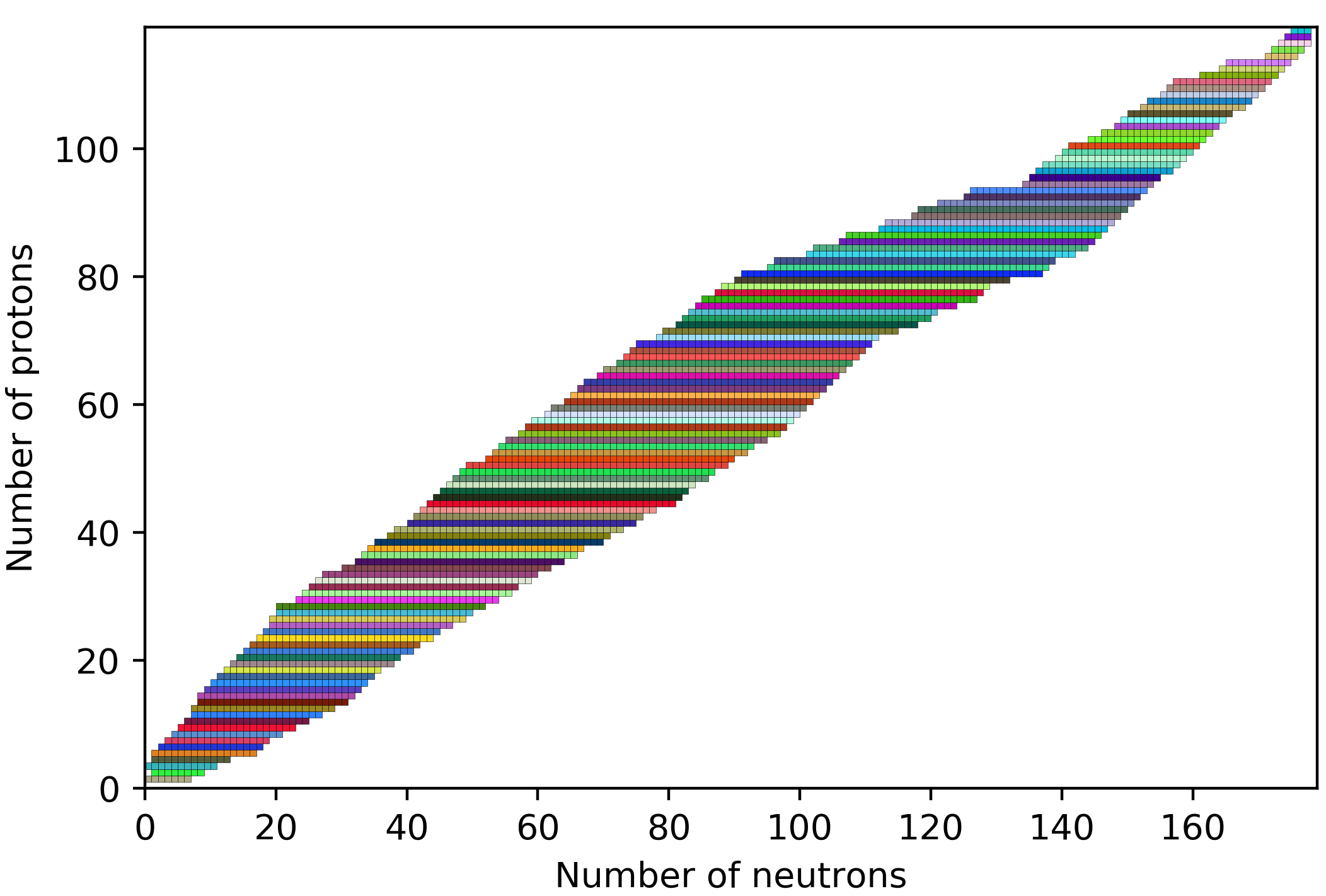

And with that, our seemingly simple life with 118 elements suddenly expanded to having more than 3000 nuclides (good news: that's a lifetime of nuclide calendars!), and that is the reason why nuclear physicists also have a nuclide chart on the wall next to their periodic table. Something like what we have below, just physicists tend to overwhelm it with additional details. In this chart, the small pixels in each row show the known isotopes of a given element (so a neutron and proton number configuration). One can certainly appreciate it as a wall carpet.

The details physicists like to place on the pixels might look like this, but usually with even more data (you can see examples and further explanation on the Live Chart of Nuclides):

But before we get too stressed about the number of possible nuclides, we can calm down a bit, because only a small portion, 339 of these nuclides are naturally occurring (252 of them are stable, the rest are radioactive). But wait, where do they come from?

As the story goes, just after the Big Bang a lot of hydrogen and helium was created due to the collisions of protons and neutrons at high energies. Then, later in stars and in the explosions of stars some heavier elements were also produced. We ended up getting a package of nuclides that we call Earth. That explains how we got stable nuclides, but what about the radioactive nuclides (or radionuclides)? Shouldn't they have decayed away on our old Earth? But first let's just quickly discuss what radioactive means.

Radioactive decay is when an unstable nucleus tries to get rid of some energy to become more stable. It is a bit like when a person needs to pee... Well, maybe not the best analogy. Nevertheless, the reason why a nucleus can be unstable is that protons and neutrons like to stay close together, but in some configurations not everyone is happy. Protons are positively charged, so they repel each other. However protons and neutrons all attract each other due to something called the strong force. These repelling and attracting forces need to be in balance, but this doesn't happen for all the possible configurations: that's when a proton, or a neutron, or sometimes a whole cluster of them (for example an alpha particle) needs to go.

For some nuclei, it is very probable that this decay will happen within a short amount of time after the nucleus was formed. For others, it might take some time to undergo decay. The probability of a decay event happening is characterized by the half-life of the nuclide. Let's say you have right now 1000 atoms of a certain nuclide in your hand, for example the iron isotope Fe-55 (the symbol refers to the element, thus the number of protons within the nucleus, in this case iron with 26 protons, and the number refers to the total number of protons and neutrons). This nuclide has a half-life of 2.7 years. Then, at random times it is going to decay, so you will have less and less iron left in your hand. 2.7 years from now you are going to have on average 500 Fe-55 atoms left (maybe not exactly, it is like a lottery). 5.4 years from now you are going to have on average 250 iron atoms left. And you probably see the pattern: 8.1 years - 125 atoms, 10.8 years, 62.5 atoms (the half atom of course is again due to the value being an average number) etc. Of course, you still have something else in your hand, since the iron isotope does not disappear, it just turns into something different. In this case it becomes a manganese isotope, Mn-55, which happens to be stable. So if you wait long enough then you will end up having 1000 Mn-55 atoms in your hand. Nevertheless, there are other unstable nuclides for which a chain of decays follows, because one decay cannot directly take the nucleus into a stable configuration.

That said, we can already suspect that one reason why we have naturally occurring radioactive nuclides is because they have such long half-lives that not all of it decayed away (for example, the half-life of the uranium isotope U-238 is comparable to the age of the Earth). Then, the next reason is that these radionuclides which were here from the birth of Earth can decay into other radionuclides. Finally, there are some naturally occurring nuclides which are created through nuclear reactions due to the cosmic radiation.

A nuclear reaction is a process when a nucleus meets with a particle, or another nucleus, and after some courting, something new is created. For example, if a uranium-238 isotope meets with a neutron, then with the right energy and with some luck the neutron can join the nucleus, and they become a uranium-239 nuclide. But, they don't live happily together for a long time, because uranium-239 has a short half-life, and it will decay, what is still followed by a whole set of events. As said earlier, these reactions can happen due to natural events. Nevertheless, nuclear reactions may happen artificially also, for example in nuclear reactors and with particle accelerators: and this is how we ended up discovering roughly 3000 nuclides which did not occur in nature. Thus, the naturally occurring nuclides of Earth self-organized themselves into humans, who built nuclear reactors to artificially create new kind of nuclides, which can have useful properties.

In this brief summary unfortunately we could not explain every concept and detail of nuclear physics. The interested reader is referred to the Guide to the Nuclear Wallchart which is an excellent resource to get an introduction to nuclear physics. We also used Wikipedia to backup our information, and the Live Chart of Nuclides for accurate nuclear properties.

We are researchers at Uppsala University working at the Division of Applied Nuclear Physics. Our research and teaching activity is centered around nuclear fission, nuclear reactor physics, nuclear safeguards and radiation measurements. During our work we have to deal with many different nuclides, mostly because spent nuclear fuel is a zoo of them. After a while we grew to appreciate various properties of these nuclides, and the perfectness of nature how the pieces of this puzzle fit together. That is the reason we wanted to share our fascination with you.

“Which is your favourite nuclide?” We asked this question to a bunch of researchers. It appears that the nuclide chart is diverse and interesting, because we got a lot of different answers, where nearly no one was the same. Special thanks to all the friends and colleagues who contributed to this collection of "interesting nuclides"!

© 2020 Zs. Elter, P. Andersson and A. Al-Adili