The claim to fame of today’s nuclide is that it is the most stable of all nuclides on the chart! So if we are going to tell you about this “the most stable nuclide”, would you already know which one that is? Surely some of our nerds in the audience already have an opinion?

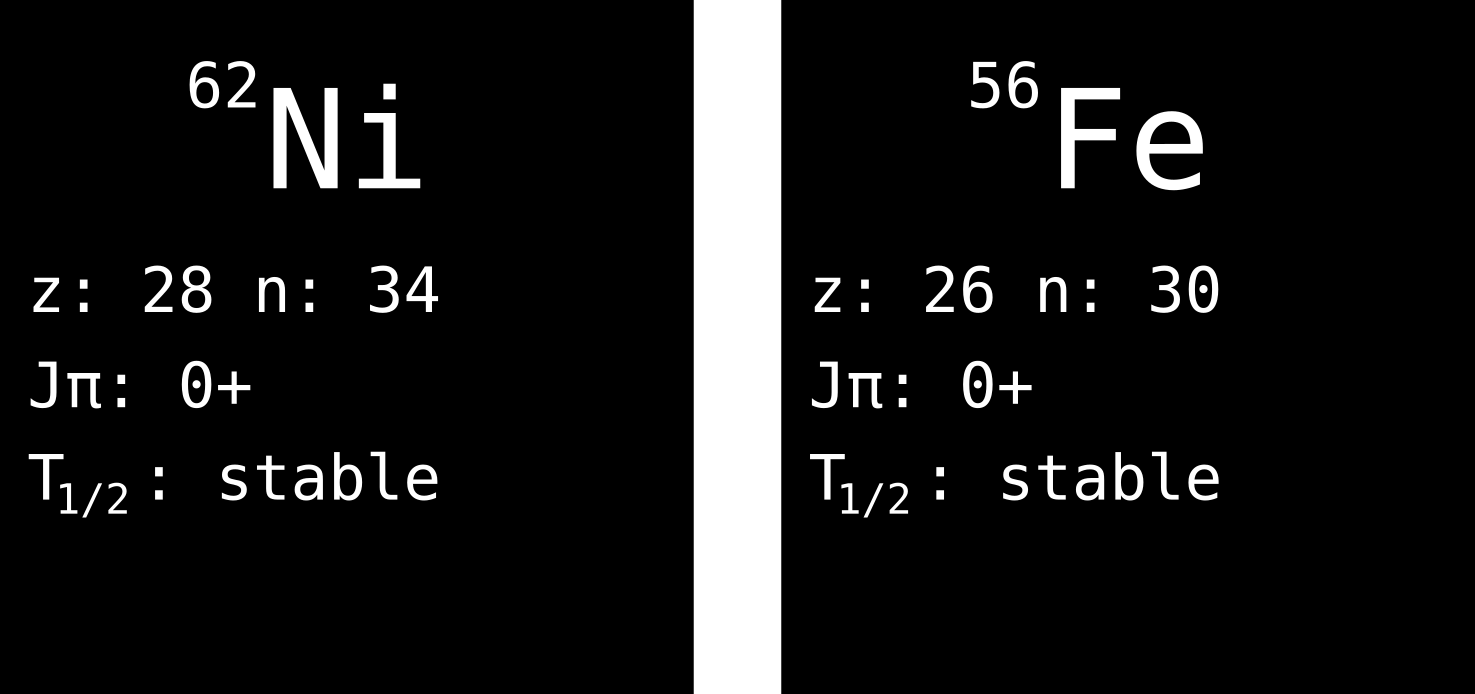

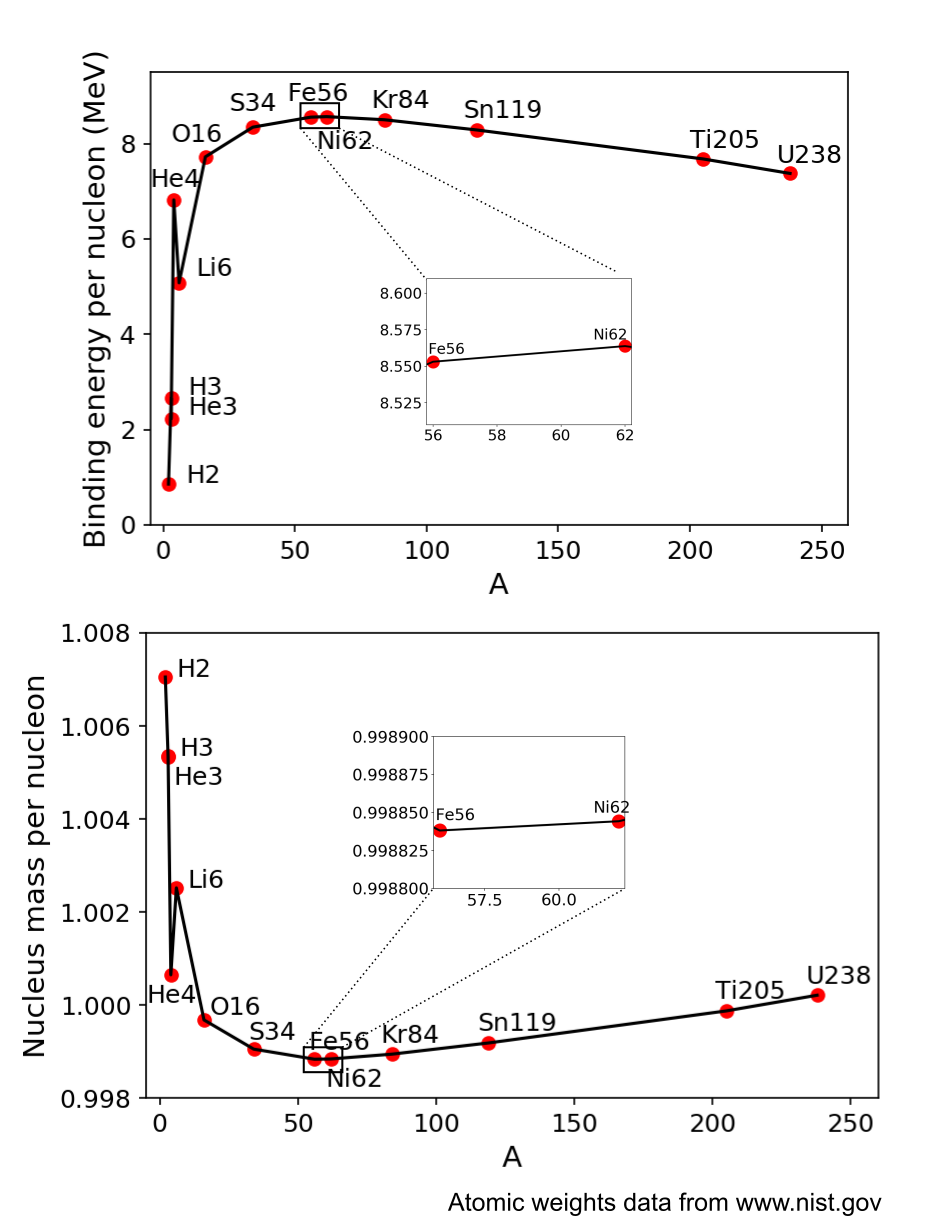

As we have discussed earlier, the protons and neutrons in the nuclei are bound to each other. And this bond is more or less tight, something that is quantified by their so-called binding energy. This is the energy that would be required to break all the protons and neutrons free of each other. Usually, the binding energy per nucleon is compared, and the higher it is, the tighter the bond of the nucleus, and the more stable the nuclide. Of all nuclides in the chart, which has the tightest bond? As many textbooks will inform, this is the well-known iron isotope Fe-56.

Unfortunately, that is not entirely correct.

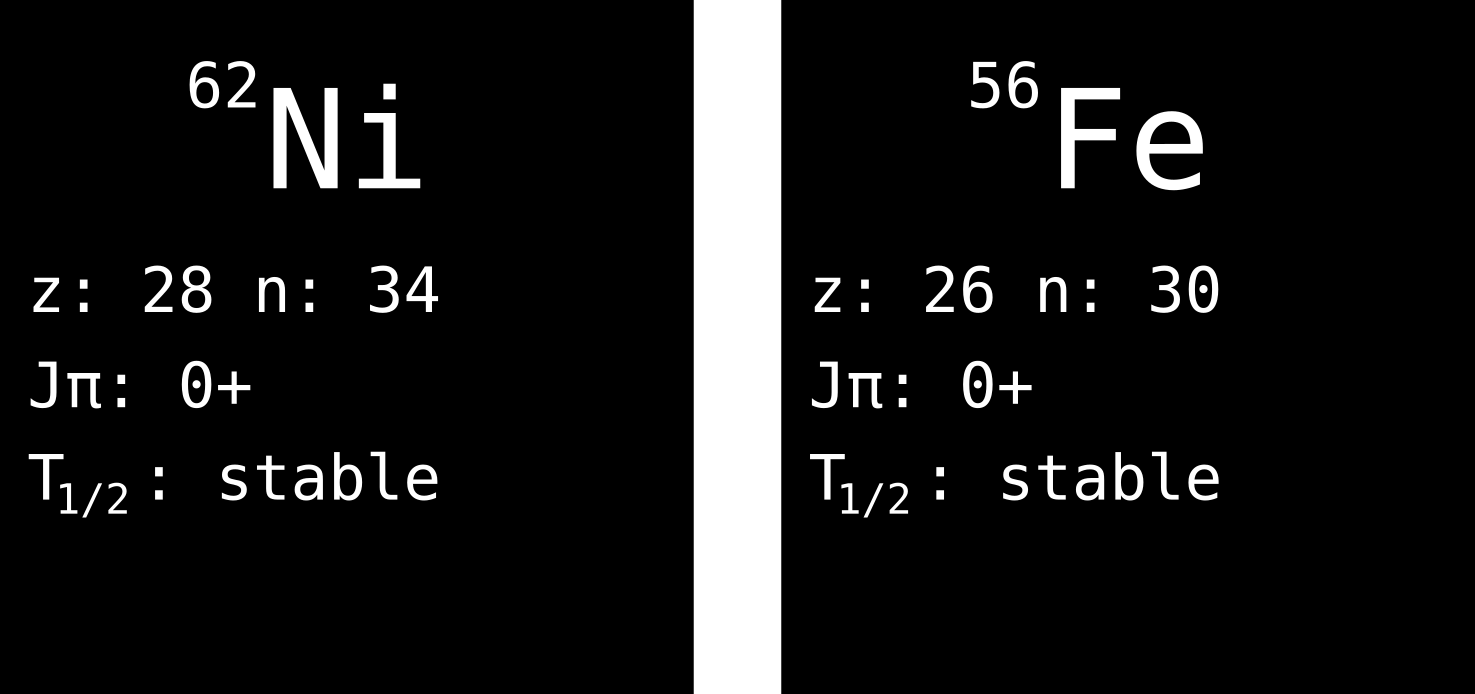

In fact it is a common misconception that Fe-56 would have the highest binding energy per nucleon. A careful review in its neighborhood in the nuclide chart reveals that Fe-58 has higher, and the highest binding energy per nucleon of all nuclides is that of a nickel isotope, Ni-62. Thus we can conclude that in fact Nickel-62 is the most stable nuclide. Right?

We came to about this point in preparing today’s nuclide, planned for December 2nd, before the serious disagreement started, causing both a severe delay of the topic, and quite vivid debates within as well as outside the little group of people behind this calendar. I usually don’t debate with my friends, I’m not triggered by politics, and couldn’t care less for sports. But when it comes to the stability of a nuclide, I pull off my imagined gloves and throw it in their faces.

So, it’s not necessarily the highest binding energy that tells us which nuclide is more stable. That was assumed without justification, although it does have some merits. The highest binding energy per nucleon figure literally means that Ni-62 is the nuclide which it takes the most energy to rip completely apart, resulting in a cloud of distant nucleons. But this is not the typical result of any common reaction or decay. In fact, looking at actual decays and reactions, there are two families, 1) redistribution of nucleons between nuclei, such as fission, fusion, alpha decay, neutron emission (in which case the only change of energy in the system is the binding energy), and also 2) weak interactions (beta-, beta+ et. c.). In the latter case, there are other changes to the total energy of the system than merely binding energy, and maybe that should not be forgotten. In particular, it involves the change from neutron to proton, or vice versa. Here, the total change of energy of the system includes a slight difference in mass between the two nucleons. What if we consider that?

Before answering, just to strengthen the case that total mass might be considered as a measure of stability, it can be reminded that beta decays sometimes happen of a parent nuclide with higher binding energy, to an offspring nuclide with lower. This is the case of the beta decay of carbon-14 and also the double beta decay of tellur-128. So it hurts a little bit to use the binding energy per nucleon as a measure of stability. The total mass of a system would on the other hand only be able to decrease in exothermic reactions or decays, so a system consisting exclusively of the nuclide with least mass per nucleon, wouldn’t that be the most stable? That cannot ever spontaneously transform to anything else in any exothermic reaction or decay? (If you don’t remember, endothermic means that energy needs to be invested in the reaction, while exothermic means that energy is released)

If we use this figure to compare the nuclides, guess what we find? Yes, it takes us right back to iron-56 again. The iron isotope has 46% protons, and the nickel has only 45%. Therefore, the lower rest mass of the iron’s protons compensates for the slightly lower binding energy per nucleon, with the result that iron-56 has the lowest mass per nucleon of all nuclides. And that means that a pure fe-56 system is unable to spontaneously transform to any other nuclides, unless external energy is available for the transformation.

But… We have to ask ourselves at this point (an upset colleague did also ask), what do we even mean by “most stable”? That’s just a semantic dispute! What we can all agree to is the following facts that are undisputable:

One can also mention that there are many nuclides that don’t have a known decay, and neither a measured half-life. Are they all equally stable perhaps? Is it like a binary property, 0 or 1, and not a property that we can compare between different stable nuclides? Both Fe-56 and Ni-62, as well as many other nuclides, are classified as stable after all. Maybe that’s right, but there could be a reason to distinguish between nuclides that will just decay too rarely for us to observe it, and other nuclides that may remain for times much, much longer than the current age of the universe.

Still, a problem is that neither of the two nuclides can easily be transmuted to the other in an exothermic reaction. There is an unbridgeable gap between the two. As noted on wikipedia, however, in principle 28 Ni-62 nuclei might fuse and then decay to 31 Fe-56, and in this process release energy. So it could happen spontaneously… if waiting long enough. Don’t hold your breath.

Looking at stellar nucleosynthesis for ideas, neither nickel nor iron is the end point of fusion in stars. One can continue to add alphas or neutrons and gain energy, to much heavier nuclei, and still have exothermic reactions. But it should be remembered that this can happen because the other reactant is much lighter, having very little binding energy per nucleon (as well as mass excess), and not because of the nickel or iron, that are already of optimal binding energy (or mass) per nucleon.

Further research (meaning to disturb other colleagues), revealed that in neutron stars, the composition in the upper crust is calculated by assuming that the most energetically favored nuclide will dominate the concentration. And this is Fe-56. So maybe that settled the question then? No, because that is only in the low density limit in the upper crust. At greater depth in the crust, and greater pressure, the Ni-62 becomes the most energetically favored state of nucleonic matter. And then, at greater depth still, even heavier and more neutron rich nuclei will prevail.

So in conclusion, what does iron and nickel have in common? Well, apart from being two shiny metals, used for thousands of years by mankind, common in steels for engineering and construction, and both being ferromagnetic… Other than all that, they can also both be said to have the most stable nuclides in the chart, with nickel-62 or iron-56!

If you want a more specific answer, pointing out a single one of the two, then you have to decide for yourself. But you better prepare for a dispute, and be it may a semantic dispute, but you better bring your boxing gloves. A special thanks today to those who have participated in the sparring.

© 2020 Zs. Elter, P. Andersson and A. Al-Adili