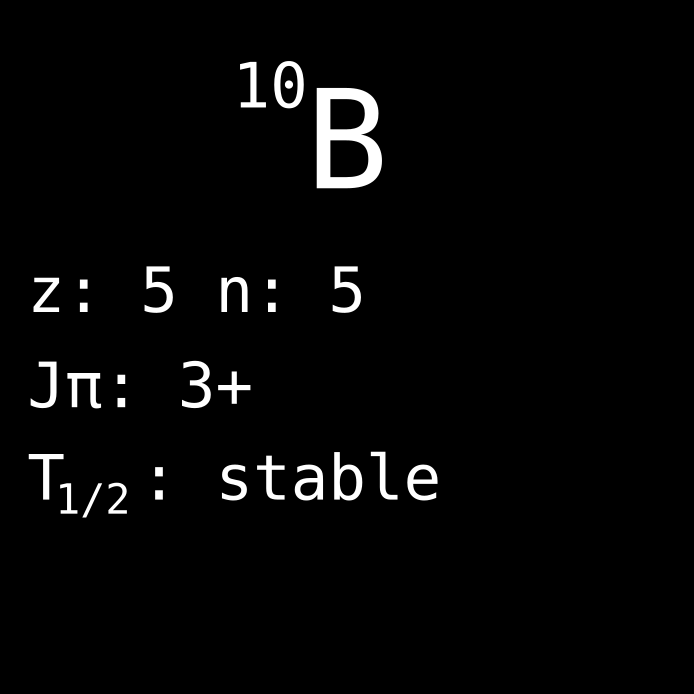

With the discovery of induced fission and the advent of nuclear reactors, not only new artificial radioactive nuclides became of interest. Also a lot of the already well-known, stable, and naturally abundant nuclides got renewed interest. Natural boron for example (atom number 5) has two stable isotopes, B-10 and B-11. Probably, nobody thought too much about them before the Manhattan project. Why did it suddenly change? The answer: Boron-10 is a reactor poison.

A nuclear reactor with a self-sustained chain reaction needs to be designed with careful consideration of the economy (meaning the neutron economy, if you thought anything else). For every neutron that causes a fission reaction in uranium-235, about 3 new neutrons will be released from the fission fragments. The neutron economy requirement is that one of these neutrons must induce a fission reaction in another uranium nucleus. Keeping one neutron for that purpose is not that easy, especially if limited to using natural (un-enriched) uranium. Consider that some neutrons will escape the reactor core, others will get absorbed in the moderator, or in the uranium-238 that makes up the majority of the natural uranium. Even if a neutron hits a uranium-235 target, more than 10 % of them don’t fission, they just become uranium-236, which is still like the original atom, but slightly heavier. Much like myself after the holidays.

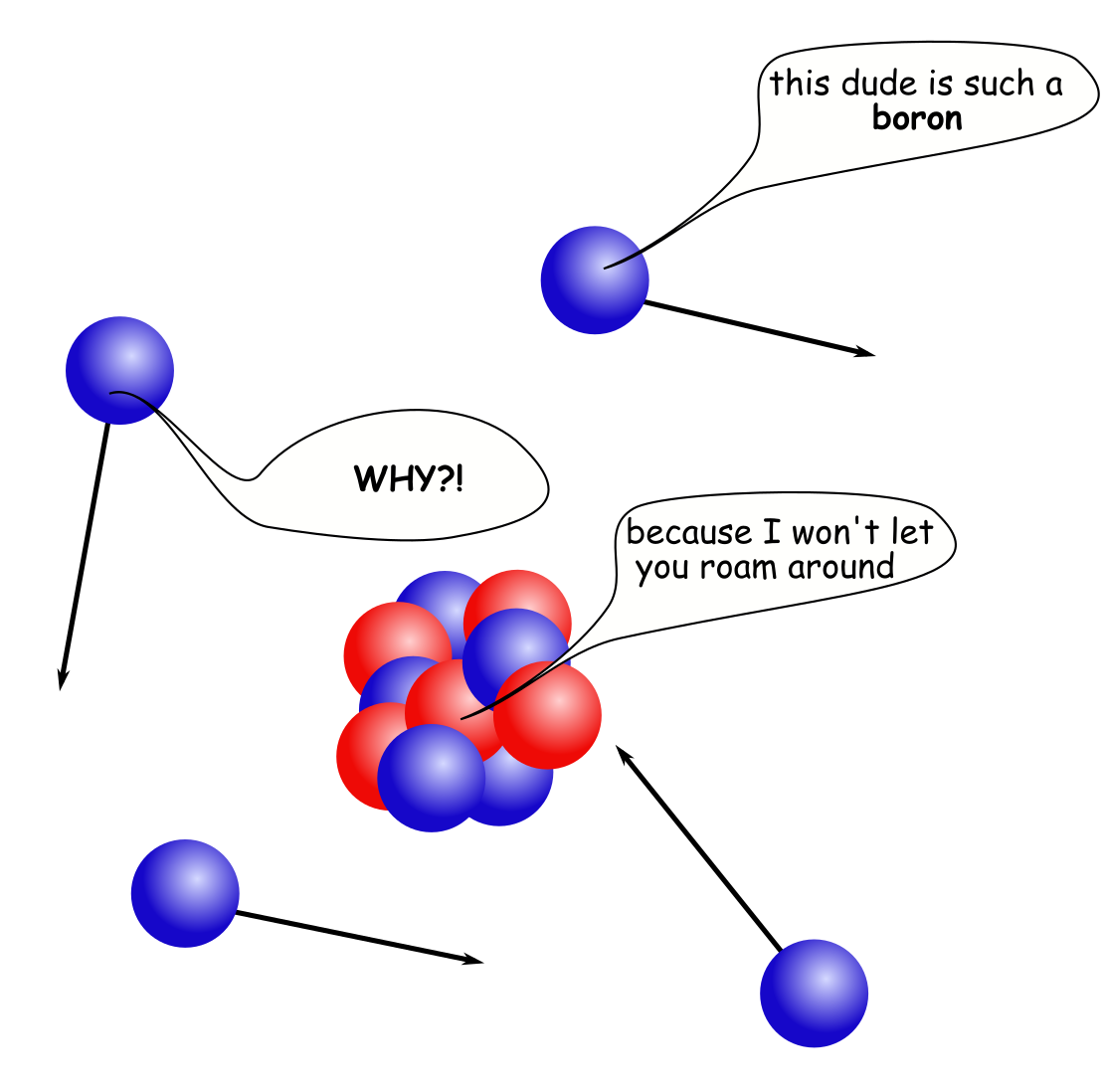

To make it possible to run the reactor, one must pay attention to avoid the unwanted loss of neutrons in reactor poisons. A poison (as you might remember from Xe-135 a few days ago) is a nuclide that is very fond of absorbing neutrons, and there are some materials out there that are really fond of eating the neutrons, boron-10 is one of them. When a boron-10 is hit by a neutron, it takes it in and emits an alpha particle in its place (i.e. a He-4 nucleus). This leaves a Li-7 nucleus remaining as the product of the reaction.

When preparing the first reactor, Chicago-Pile 1, which was moderated by graphite, the physicist Leo Szilard found that trace contamination of boron in the graphite was ruining the chances of succeeding with using it in a nuclear reactor. Therefore he invented the solution of measuring the damping of neutron radiation from an external neutron source in the graphite from all suppliers, to qualify it for use in the reactor. This way, they managed to overcome the neutron poison problem. On the contrary, in the German nuclear fission research, they deemed the graphite to be unfit as a choice of moderator, and were forced to go for use of heavy water, that is more difficult to produce.

Nowadays, Boron-10 is used heavily in nuclear reactors, as an intentional poison, an absorber used to control the chain reaction. As such, it is introduced in a controlled manner into the core; mixed in the cooling water, embedded in control rods inserted into the core, or in burnable absorber rods mixed with some of the fuel. Here, the plan is quite the opposite, to decrease the reactivity of the core, because remember that the core needs to be operating for some time, and acquiring some depletion of the uranium in the fuel. Therefore, the fresh fuel needs to have excess reactivity (more than needed to obtain the self-sustained chain reaction). The boron absorption lowers the reactivity in the freshly refueled core, but is burned up or extracted after some time of operation of the fuel. This allows for long cycles of operation without refuelling.

As mentioned above, after capturing the neutron, an alpha particle is emitted. This fact makes Boron-10 also well suitable as a deposit in ionization chambers to detect neutrons: the neutron hits the boron deposited on one of the electrodes, and the emitted alpha particle ionizes the filling gas of the chamber which in turn produces a measurable electric signal. Such detectors can be used for example to monitor the flux level in a nuclear reactor.

Also in medicine, the cancer therapy method of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy is a promising technique. In this therapy, a B-10 carrying a chemical agent that seeks up the tumor is administered to the patient, and subsequently, the patient is irradiated with a controlled dose of neutrons. Since much of the radiation dose received by the patient is from the alpha particle, the harmful radiation dose is focused where it is needed, in the tumors, and much less anywhere else. This is a promising treatment for brain and neck tumors, however, hindered by the scarceness of suitable strong neutron sources.

© 2020 Zs. Elter, P. Andersson and A. Al-Adili