Xenon is a noble gas, because it's outer electron shell is full. Due to this, xenon (and other noble gases) generally do not participate in any chemical reactions. Another consequence is that xenon is non-toxic. But enter the beautiful world of nuclear physics, and it turns out that the isotope Xe-135 of our seemingly innocent gas is a reactor poison and one of the culprits behind the Chernobyl disaster.

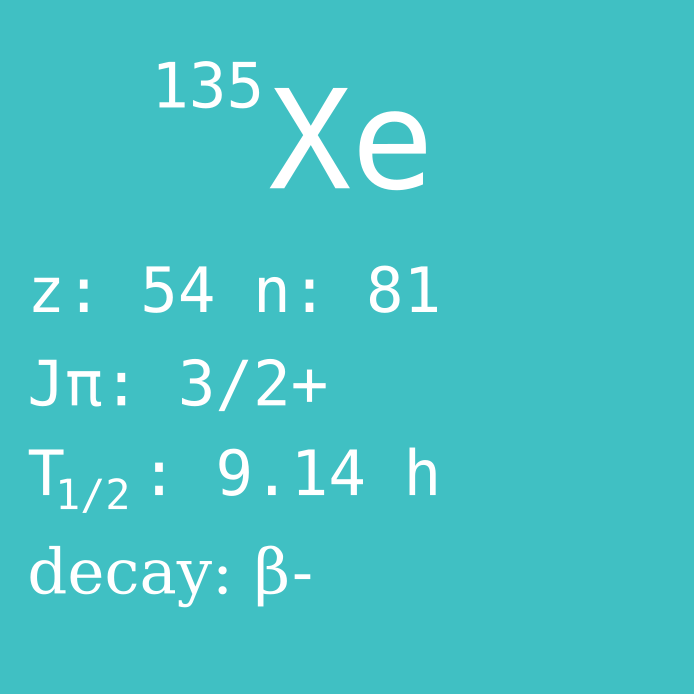

As we discussed earlier there are certain magical numbers of neutron and proton numbers in the nucleus. If you recall, one such number was 82, and our nuclide of the day happens to have 81. Capturing one more neutron makes this nuclide magic, and also even-even (in proton and neutron numbers), and nucleons like to be paired. The Xe-135 nuclei really like to take on another neutron, if it dares to go too close. With that we see why they can be called poison: they absorb neutrons in the reactor even if we do not want them to do so, which can cause a reactor to shut down unless compensated for in some manner.

But we still have to discuss why there is any Xe-135 in the reactor? Xe-135 is produced through two main pathways in a reactor: there is a tiny chance that it gets produced directly in fission (when the U-235 nucleus splits into two fragments), but also, there is a great amount produced by decay of iodine-135, of which much more is created by fission of the uranium. But the concentration of Xe-135 in the reactor is not ever-increasing, instead it reaches a balance, where the production is matched by the loss rate, in an equilibrium concentration. The Xe-135 is radioactive, so it decays steadily, and since it also is so fond of neutrons, the capture reactions will also consume Xe-135. During full power operation, when there’s a lot of neutrons to capture, that will be dominating.

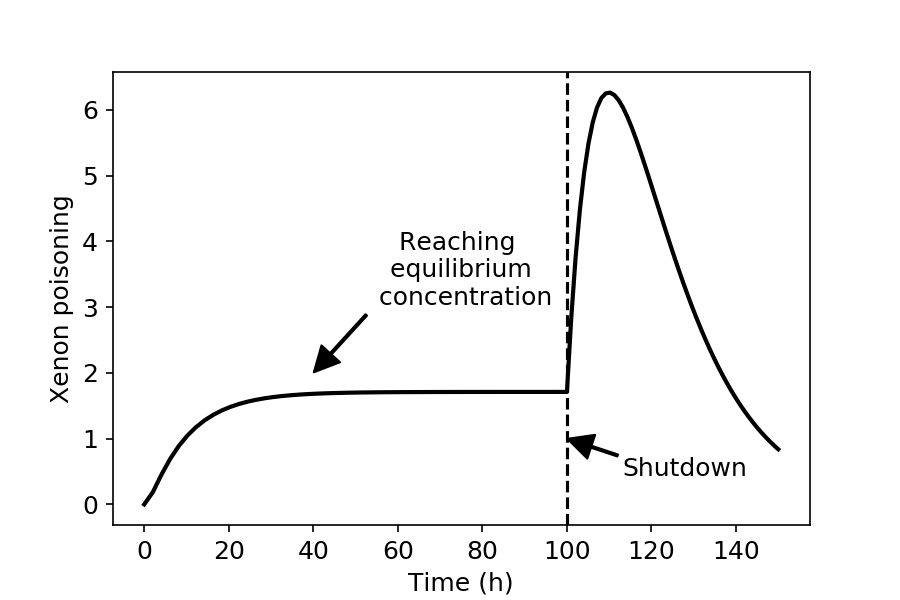

The iodine pit is an interesting phenomenon that takes place when the reactor comes to a stop. At that time, the production term from fission as well as the loss term due to neutron capture disappear, and all what's left is the dominating production term due to the decay of I-135 (half-life is 6.58 hours), and the slower loss term due to the decay of Xe-135 (half-life is 9.14 hours). Because of this, the Xe-135 concentration will at first increase. A maximum (the xenon peak) is reached when there is not enough I-135 left, so the Xe-135 decay will dominate the further evolution of Xe-135 which will then drop. When the Xe-135 concentration is above the equilibrium level corresponding to the full-power operation, we say that the reactor is poisoned. During this time it is difficult to restart the reactor (although in principle possible by removing other neutron absorbing components, for example control rods, from the reactor). Therefore, the xenon peak has the practical consequence that if the reactor needs to be shut down for any reason, it can’t be restarted for around a day, until the xenon peak decays away.

It has to be noted that the xenon peak also occurs when the reactor power is only reduced: in this case the loss terms due to neutron capture does not disappear, but decreases, whereas the production term from the decay of I-135 does not change. The time evolution of xenon poisoning in a reactor is shown in the figure below. After startup, the concentration of xenon-135 increases until it reaches equilibrium. When the reactor is shut down (100 hours after startup) the xenon-135 concentration first increases, and only cca 8-10 hours after shutdown will it start decreasing again. During the xenon peak it may be difficult to obtain a sustained chain reaction.

And with that explanation we have arrived to Chernobyl, where xenon poisoning was one of the contributing causes leading up to the disaster. The day before the accident the power of the reactor was reduced because the operators planned to perform a test at low power. However, the power grid controllers in Kiev asked the operators to postpone the test, thus for several hours the reactor was operated at 50% power. During this period of reduced power operation, the Xe-135 concentration started to increase and the operators decided to compensate by withdrawing control rods from the reactor. As a result, the reactor was in an unusual state where design flaws, that the control room staff appears to have been unaware of, made the reactor unsafe. In that way, the xenon played a role in the chain of events leading up to the explosion.

© 2020 Zs. Elter, P. Andersson and A. Al-Adili